Ce texte a été initialement publié dans une forme légèrement différente dans Artforum 41, no. 7 (March 2003): 63, 65–66, 260–61, 264. Il est ici repris avec la permission de l’auteur et de l’éditeur.

Le critique d’art et historien de l’art James Meyer s’est vu confié la collection de diapositives de Craig Owens par Scott Bryson, le compagnon de ce dernier, au cours des années 1990. Quelques années plus tard, il ose ouvrir ces boîtes en carton. Dans ce texte, James Meyer en propose une traversée s’arrêtant sur des images d’œuvres connues et d’autres moins connues et, ce faisant, retrace le parcours intellectuel du critique d’art.

For a critic, a slide collection is the most personal of artifacts. These are the images set aside to remember; here is the record, in miniature, of a life in art—slides acquired in the process of writing review after review or making ubiquitous visits to the galleries. A slide box is a seedbed of the imagination, a record of memory, a resource. Its contents beg to be arranged into so many narratives of art history—articles, books to be written one day. Most never come to pass. The idea doesn’t test out. The art suddenly looks stale. Time is short.

The slide is a passé technology. The last vestige of the bulky, black-and-white lantern plates of the nineteenth century—still found in the grand art history departments, which do not quite know what to do with them—the Ektachrome is rapidly being replaced by the thumbnail JPEG, the carousel projector by PowerPoint. Next to the digital image the slide is a delicately tactile thing, a ribbon of film pressed between glass slivers. It easily shatters. It fades. Already it seems of another time: the midcentury moment of art history’s rise as an academic discipline, the era of Panofsky and Schapiro and Gombrich, of the Western survey and midday lecture (lights dimmed) once referred to as “Darkness at Noon.”

I am sorting through the slide collection of Craig Owens, the remarkable art critic and teacher who died of complications from AIDS in 1990. One day, Owens’s partner, the French literature scholar Scott Bryson, presented me with a bulky sack. (A friend had brought me to visit.) “Craig’s slides.” I did not know what to say.

After all, I never met Owens. He was, during my student days, one of the few critics I read with avid attention. Along with his colleagues associated with October during the late 1970s and 1980s (when that journal was at the forefront in theorizing the various phenomena that came to be known as postmodernism in the visual arts), Owens raised art criticism, a practice Clement Greenberg once dismissed as a lesser form of literature, to a level of uncommon seriousness. Far more than mere reportage or promotion, his best essays are passionate expositions. In their intensity, their conviction, their self-awareness, his writings suggest a utopic belief in criticism as a redemptive form—as if one could write one’s way to a more just existence. This notion of criticism as a life lived critically, of being a critic (a legacy of the Frankfurt School, of the New York Intellectuals) has been in retreat for some time. The nature of this withering is complex. It needs to be recognized, and addressed.

It was a long time before I dared peek at the metal containers and musty black cardboard boxes bearing Owens’s name. If a critic’s slides are indeed so personal, rifling through them would feel slightly indecent. My hesitation to do so had another source, however: the feeling of paralysis that hit me whenever I tried to contemplate the critic’s death. There is no way to understand someone dying at thirty-nine. “There is no reason that explains AIDS,” Gregg Bordowitz has written. “There are historical, material conditions that create a situation of crisis, but there is no reason why some people die, why some get sick.”1 During the height of the AIDS epidemic in this country (the disease had by then become a global pandemic), one faced this conundrum daily. The deaths of many friends in their twenties and thirties remain, for me, impossible to comprehend. The sudden arrival of Owens’s slides was disconcerting. And so I stored the little boxes in a drawer and, for a while, tried to forget about them.

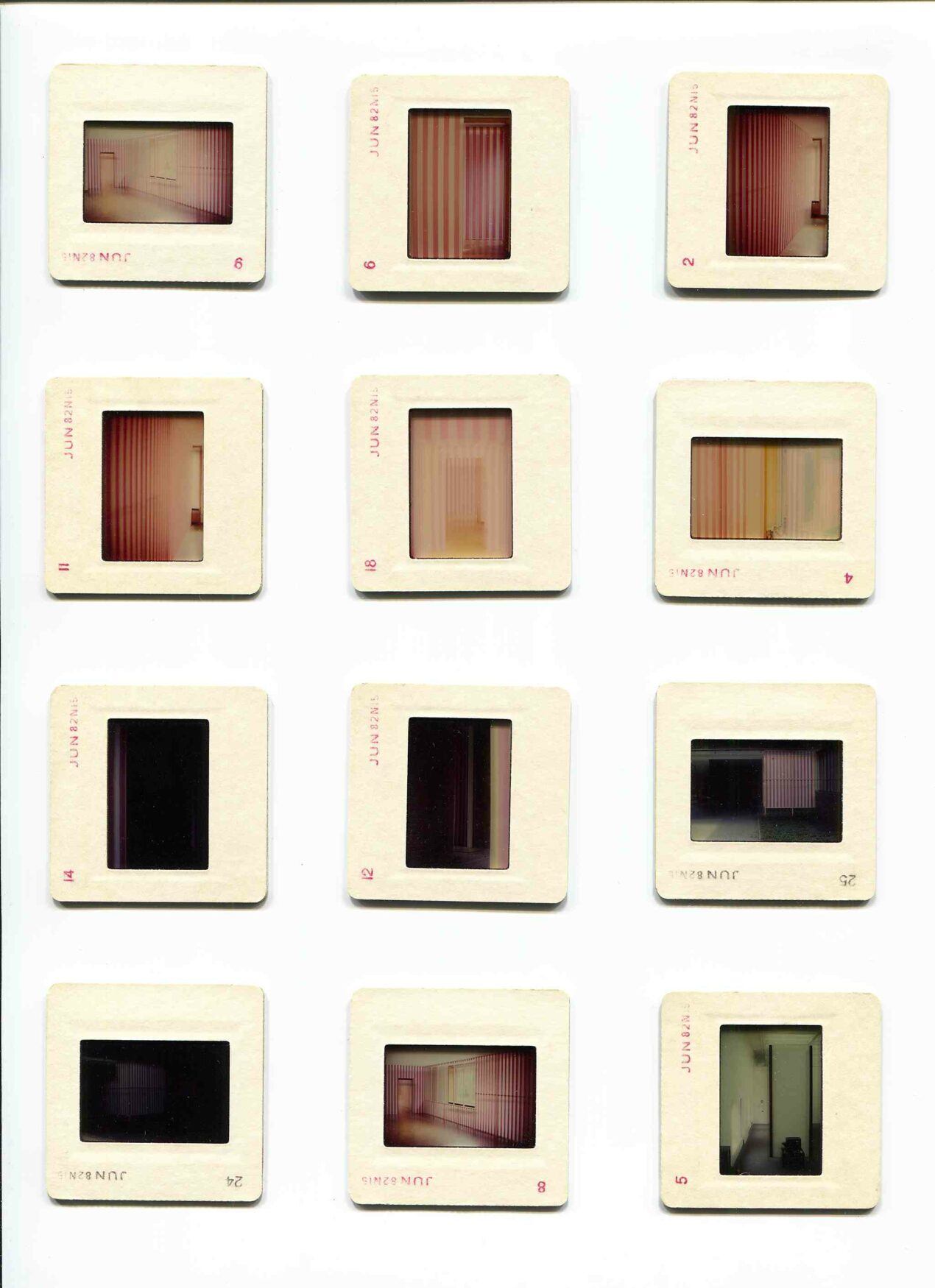

Les diapositives de S280, S281 et S282 de la collection de Craig Owens conservée par James Meyer à Washington D.C.

Eventually curiosity won out—and my own scruples. To hide the archive away was not an option, for it meant consigning this small evidence of a keen critical mind to a quiet oblivion. I began to study the slides one by one. I pull out a good twenty images of Daniel Buren and Michael Asher’s installation at the Haus Esters and Haus Lange at Krefeld in 1982. The slides are unbound, without glass, and unlabeled. It would appear they were shot by Owens himself. Clearly, he wanted to remember the show well: the slides record the installation from every angle. Here is another Asher: the artist’s Van Abbemuseum project of 1977, which entailed removing the ceiling glass panels on one side of the museum before the show’s opening and replacing them during the span of the exhibition. The other half of the museum contained selections from the permanent collection installed, according to Asher’s conception, by the director.

Owens, writing on the Van Abbemuseum piece in “From Work to Frame,” admired the way Asher “exposed to public view” “activity which is usually completed before an exhibition opens.”2 He appreciated the manner in which the simple process of replacing the ceiling glass “contrasted . . . the static quality of the more traditional installation that accompanied it.”3 The two halves of the show revealed, through opposition, the museum’s normative practices. As I examine the boxes I locate other works discussed in “From Work to Frame,” Owens’s most sustained exposition on institutional critique: Buren’s Within and Beyond the Frame (John Weber Gallery, 1973), involving the suspension of the artist’s striped canvas banners from SoHo’s principal gallery address, the 420 building, across West Broadway; Louise Lawler’s first show at Metro Pictures (1982), an arrangement of works by other gallery artists; and Hans Haacke’s Visitors’ Profile, 1972, from Documenta 5 (a statistical documentation of the audience of international art shows), MetroMobiltan, 1985, and Voici Alcan, 1983, which map the ties that bind cultural institutions to multinational sponsors and, at times, unsavory political regimes (here, apartheid South Africa).

Les diapositives S515 et S516 de la collection de Craig Owens conservée par James Meyer à Washington D.C.

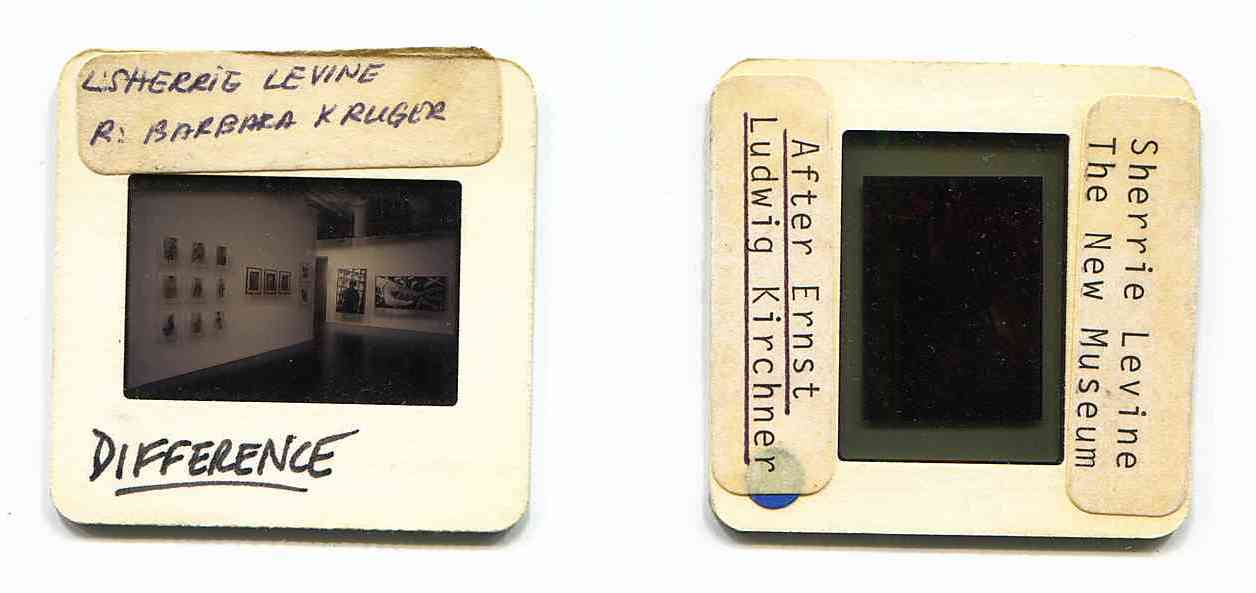

Institutional critique, the contextual analysis of art’s production and display, was but one of the tendencies examined in Owens’s writing. Appropriation was another: scattered throughout the slide boxes are Sherrie Levine’s collages of mothers and models framed by presidential silhouettes, Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills,” 1977–80, and numerous Barbara Krugers. Owens initially favored appropriation for its capacity to expose the rhetorical conventions of expressionism and documentary and the fictions of authenticity (of gesture, of the Real) implied by these formats. Levine’s knockoffs of Egon Schiele self-portraits and rephotographs after Walker Evans’s images of sharecroppers from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, amply demonstrate this argument, an argument developed in concert with fellow CUNY graduate students Douglas Crimp, Benjamin Buchloh, and Hal Foster under the tutelage of Rosalind Krauss (in a 1984 video interview with Kate Horsfield and Lyn Blumenthal, Owens characterized his early work as “a series of footnotes to [Krauss’s] writing, writing in the margins of her writing”).4

Owens, though, came to see this account of appropriative tactics as excessively narrow. The anti-expressionist reading of Levine was “insufficient,” he stated in a review of the artist’s 1982 show at A&M Artworks, because it “neglect[ed]” other “thematic concerns”5 of her work, such as the feminist content of the presidential collages. Long a devotee of Roland Barthes, Owens understood that the appropriation of mass-culture imagery offered a useful tool for examining various codes of representation, including gender. He became a champion of Levine, Sherman, and Kruger because their art registered this recognition.

I take out one slide after another to find a treasure trove of Richard Princes. I am struck by the paucity of images of women for which the artist became known. Owens preferred Prince’s pictures of heterosexual couples—all-American newlyweds, British aristocrats, and the copulating swingers from the artist’s deliciously filthy “Holiday” series, 1980–81, that picturing of Plato’s Retreat abandon. Above all, Owens seemed intrigued by the shots of isolated tokens of masculinity (gold pens, cigarette lighters) and of male models sporting three-piece suits and opulent Dry Look coiffeurs. Posed alone or in homosocial pairs, these cyphers of pomaded machismo cause one to wonder whether Owens, who mentioned Prince’s work only once in his critical writings, had been planning an essay on the artist’s appropriated representations of masculinity.

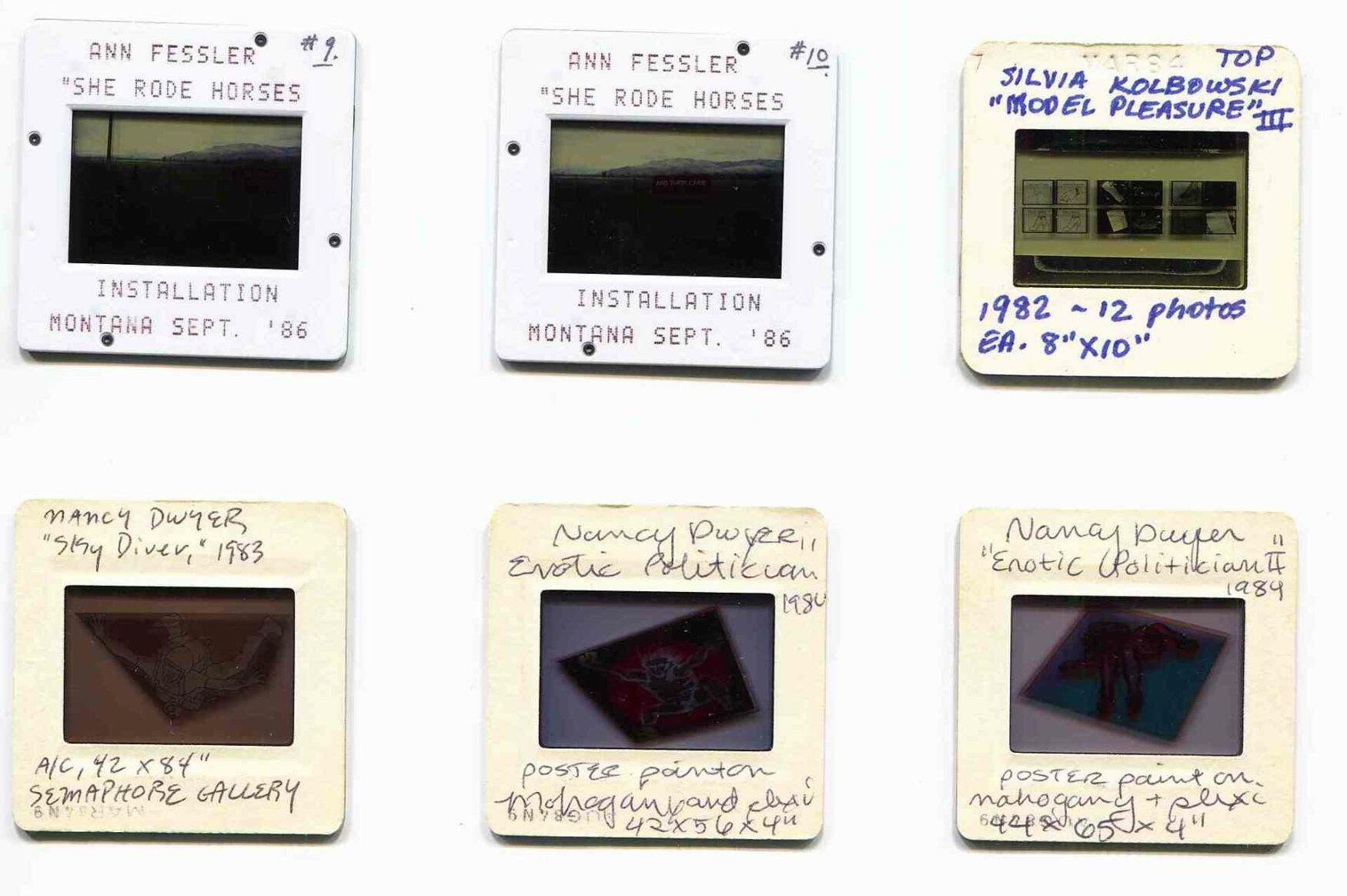

Les diapositives S427, S428, S429, S430, S431, S432 de la collection de Craig Owens conservée par James Meyer à Washington D.C.

Then there are the curiosities I don’t know. Take the slide showing Ann Fessler’s She Rode Horses, 1986, a row of red signs with white letters arranged sequentially in a Montana field. Fessler’s work is less technically sophisticated and more autobiographical than comparable projects by Kruger or Jenny Holzer of the same vintage. The text may be derived from a prior source, but it reads as a personal narrative:

WHEN SHE WAS YOUNG / SHE RODE HORSES / THE BOYS SAID / THEY KNEW WHY / BUT THEY WERE WRONG / SHE RODE HORSES BECAUSE / SHE WANTED CONTROL / OVER SOMETHING VERY POWERFUL / LIKE BOYS / AND THEIR CARS

She Rode Horses sits uneasily within the narrative of “The Discourse of Others,”6 Owens’s most important discussion of feminist appropriation. Unlike the art he favored, which de-emphasized personal narrative, Fessler’s work points back to the confessional strain of first-generation feminist practice and ahead to the recovery of this mode of address by 1990s artists (early Sue Williams, Tracey Emin). Other works are even less easy to place: Nancy Dwyer’s schematic, figurative images of sky divers and coronary patients, Thomas Lawson’s paintings with red figures on dark grounds, Gary Hallman’s billboards of enlarged photographs, Dorit Cypis’s 1982 projection The Quest of the Impresario: Courage. (Well documented in Owens’s archive, the last was reenacted as a multimedia performance with an actor playing Michel Foucault.) Now obscure, such projects, combining a variety of tactics (painting and the “Picture,” in the case of Dwyer and Lawson), show that the postmodern field was less rigidly defined in the early 1980s than we may imagine it to be. Yet the fact that Owens never mentioned these artists in prose (apart from a passing dismissal of Lawson, along with David Salle, as “painting’s supposed ‘deconstructors’”)7 confirms the impact his criticism ultimately had in shaping the canon as we know it.

Instead of the formal quality sought by modernist critics, Owens and his peers valorized a demonstrably critical art. The October critics, for instance, fashioned a dyadic model of “two” postmodernisms out of an unruly East Village scene—the “resistant” activity engaged in a critique of representation and the art institution (associated in particular with Nature Morte) and the affirmative stance entailing, even championing the return of retrograde representational means and subject matter in the form of neo-expressionism (equated with Fun Gallery and Gracie Mansion, among others). This schema, which extended the divide that opposed Pictures artists like Sherman, Jack Goldstein, and Troy Brauntuch to Salle, Julian Schnabel, Eric Fischl, Susan Rothenberg, and Sandro Chia (artists who are also abundantly represented in Owens’s collection), remains useful, but only to a point. For example, the illustration-derived paintings of Lawson, Dwyer, and certain works by Salle, may be discussed in terms of the Picture, troubling the anti-painting bias of that construction. The artists who did “fit” the model had complex affiliations as well. Both Kruger and Salle, former graphic designers, appropriated the media’s sexist imagery in their work. The fact that Kruger and Levine eventually exhibited in the same blue-chip gallery with Fischl and Schnabel, or that Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills” came to be more highly valued than much neo-expressionist painting, suggests that overlaps of taste and consumption were more complex than the polemics of those years could admit.

Owens was himself a contradictory figure. In the critic’s arresting portrait by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, we discern a striking young man with a broad nose and high forehead. His shirt is starched, his tie knotted, his jacket is tweed. Leaning forward, he fills the frame. It’s tempting to imagine that Owens, who once wrote an essay entitled “Posing,”8 is trying to manipulate the image in some way—playing The Critic for Greenfield-Sanders’s lens. (The portrait is part of the photographer’s “Critics” series.) In fact, Owens, at six-foot-seven, was too tall for the camera that Greenfield-Sanders then used; he had to be photographed seated. Bordowitz, a former student, recalled:

Craig was all arms and legs. His body movements were expansive, and he was often too large for the small chairs and furniture in the classroom. Of course, I remember him as larger than life. He was luminescent. Vibrating with energy. I always felt when I was studying with him, or watching him present on a panel, that I was witnessing brilliance.9

It’s hard to know whom we’re looking at: aesthete, activist, scholar, dandy. (Mark Dion, another former student, recalls the critic as “impeccably dressed.”10) His fashion-mindedness extended to intellectual pursuits: few art critics have had a more eager grasp of current philosophical and literary models. Theoretically there was not one Owens but several: the deconstructionist Owens, who translated a section of Derrida’s “Parergon;”11 the psychoanalytic Owens of “The Medusa Effect, or, The Specular Ruse” (on Kruger);12 the feminist Owens, whose “Honor, Power, and the Love of Women”13 and “The Discourse of Others”14 shifted the terrain of postmodernist criticism to encompass questions of gender; and the queer Owens of “Outlaws: Gay Men in Feminism.” Marx, filtered through neo-Marxists Louis Althusser and Fredric Jameson, was never far from Owens’s mind. He hoped to write a book entitled The Political Economy of Culture, an analysis of the art world’s financial and ideological location. He never managed it: all we have is the syllabus for a course of the same name and, in the boxes of slides, innumerable images of work by Warhol—“Disasters,” “Soup Cans,” and “Marilyns.” (The book’s opening chapter was to have been devoted to the Pop artist.) If these theoretical shifts suggest a disconcerting trendiness, they also point to Owens’s intellectual vitality, his restlessness, his belief in theory itself: having perceived the limitations of one model, he hoped to find a better solution in the next.

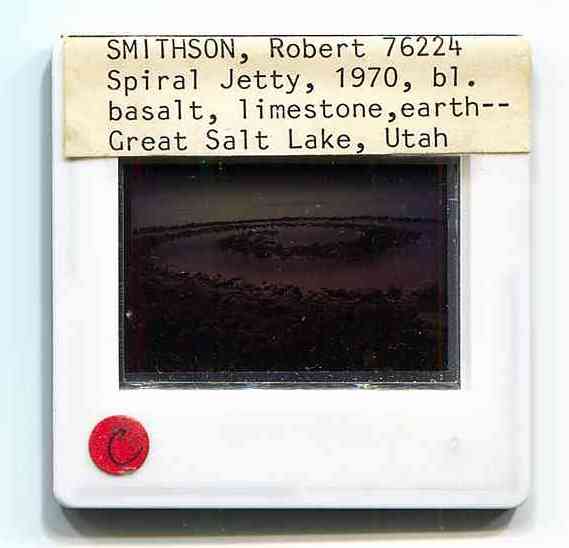

La diapositive S199 de la collection de Craig Owens conservée par James Meyer à Washington D.C.

Here is a slide picturing Robert Smithson’s A Heap of Language, 1966, a drawing of synonyms for the word “language” stacked in a pyramidal pile. I find several shots of Spiral Jetty and an image of mirrors embedded in sand from Smithson’s 1969 Artforum article “Incidents of Mirror Travel in the Yucatan.” In “Earthwords”—a review of Smithson’s writings that remains one of the critic’s finest efforts—Owens speaks of the artist’s “dazzling orchestrations of multiple, overlapping voices.”16 Rather than a “discrete” sculpture, he describes Spiral Jetty as a “link in a chain of signifiers which summon and refer to one another . . . a potentially infinite chain extending from the site itself . . . to quotations of the work in other works.”17 Owens could well have been describing his own practice. His lectures are recalled as bravura events “drawing from a limitless source of references;”18 his most ambitious texts are layered with allusion. “The Allegorical Impulse”19 alone demands acquaintance with Barthes, Paul de Man, Walter Benjamin, Joel Fineman, and Edgar Allan Poe (to mention only some of its citations), and thus embodies, in its fragmentary structure, in its palimpsest of references, the allegorical model of meaning that Owens equated with Smithson’s practice and with postmodernism in general—of images and texts pointing to previous images and texts, of a signification without origin or end. “The Allegorical Impulse” wears its erudition on its sleeve. Some of its references are dubious, indeed perverse (Owens’s account of modernism conflates Kant’s notions of judgment and pure reason, when they are distinct for the philosopher). Yet it is an essay with an argument about representation and history; it divides a modernist model of reflexivity from a postmodernist, deconstructive semiosis. It concludes ambitiously:

This deconstructive impulse is characteristic of postmodernist art in general and must be distinguished from the self-critical tendency of modernism. Modernist theory presupposes that mimesis, the adequation of an image to a referent, can be bracketed or suspended . . . When the postmodernist work speaks of itself, it is no longer to proclaim its autonomy, its self-sufficiency, its transcendence; rather, it is to narrate its own contingency, insufficiency, lack of transcendence.20

Many of Owens’s slides bear the stamps of the various institutions where he taught (the boxes labeled ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO PHOTO AND SLIDE DEPT. were no doubt pilfered as well). Teaching, for Owens, was a means of survival, but it also meant something more. Not only a laboratory for testing out ideas (the section on Owens’s pedagogy in Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power and Culture, the collection of his writings published in 1992, includes a wide-ranging selection of syllabi), the classroom was a dynamic site in which distinctions between theory and production, between the roles of critic and art student, were blurred. “Teaching,” the book’s editors, Scott Bryson, Lynne Tillman, Barbara Kruger, and Jane Weinstock, note, “was a necessary part of his project. He always questioned the arbitrary separations between and among theories and practices.”21 Andrea Fraser recalls:

I ended up in Craig’s “Ideas in Art” class by accident. I was still seventeen and just starting my second year at SVA. He began the first class with a critique of the relations in the classroom—of how his position of authority was established in its spatial and specular organization, of how knowledge was a form of power and so forth—concluding with an acknowledgment that such a critique, in and by its articulation, would not necessarily function to disrupt such relations of power. I remember feeling that I had found what I was looking for.22

Owens left his mark on those who studied with him. One may still discern the evolution of his allegorical concept in Collier Schorr’s photographs and texts, which unsettle fixed structures of identification and desire, and Fraser’s performances, which fuse the speech of museum staff, patrons, and artists into grotesque combinations. Dion’s examination of representations of nature by way of text, object, and image; Tom Burr’s multimedia archaeology of gay male history; and Bordowitz’s dissections of media depictions of AIDS, suggest an integration of the thinking of Foucault—Owens’s greatest lodestar—whose writings assert that nature, sexuality, and disease are not physical “truths” but historical, discursive categories.

Les diapositives S91, S92, S93 de la collection de Craig Owens conservée par James Meyer à Washington D.C.

Here are slides documenting Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document, 1973–79, and Martha Rosler’s Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75. The connection Owens perceived between these two extended beyond their feminist engagement. He was concerned with their method—an approach he came to call “critical practice.” The psychoanalytic account of motherhood developed in Kelly’s work, Owens asserted, was not simply an application of psychoanalytic theory. Rather, Kelly’s project entailed a rethinking of psychoanalytic concepts. Post-Partum Document was “a mother’s interrogation of Lacan, an interrogation that ultimately reveals a remarkable oversight within the Lacanian narrative of the child’s relation to the mother—the construction of the mother’s fantasies vis-a-vis the child” (italics mine).23

Testing theory by practice, Kelly’s work was itself a “theoretical investigation,”24 a critical practice that blurred static “division[s] of labor—artist/critic, theoretician/historian,”25 as Owens told Anders Stephanson in a 1987 interview. Similarly, in “The Discourse of Others,” the critic noted that Rosler’s essays on documentary photography were “a crucial part of her activity as an artist.”26 Just as Rosler’s writings theorize the refusal of authorial mastery that photo-documentary implies, so too her Bowery work disrupts that form’s conventions (the “neutral” shot and caption that establish a purported truth) through the conjunction of two “inadequate” representations: photographs of skid row absent of drunks set against the cliched barbs (“stewed,” “pickled,” “canned”) once used to describe them.

“Critical practice” was one of Owens’s more radical proposals, for it meant nothing less than a reconception of artistic work and artistic identity. It implied a range of related activities—art-making, teaching, writing, political engagement—as occupying an equal status (traditionally, only the artist’s “creative” work is valorized). It could also suggest a rethinking of the critic’s role: if the distinction between theory and practice were blurred, the critic’s practice could be seen as “parallel” to the artist’s rather than antagonistic. Owens’s idealistic speculations were hardly new, if one recalls Benjamin’s Artist-as-Producer, the 1960s concept of the “art worker,” or Lucy Lippard’s early efforts to align her criticism with the experimental efforts of language-based Conceptualism. But he made these concepts new for his time and for those with whom he came into contact. The multitiered practices of Bordowitz (video, activism, teaching, writing) and Dion (installation, collaborative “digs,” environ mental pedagogy), for example, can be discussed in these terms.

S199, Collection de diapositives de Craig Owens, conservé par James Meyer, Washington D.C.

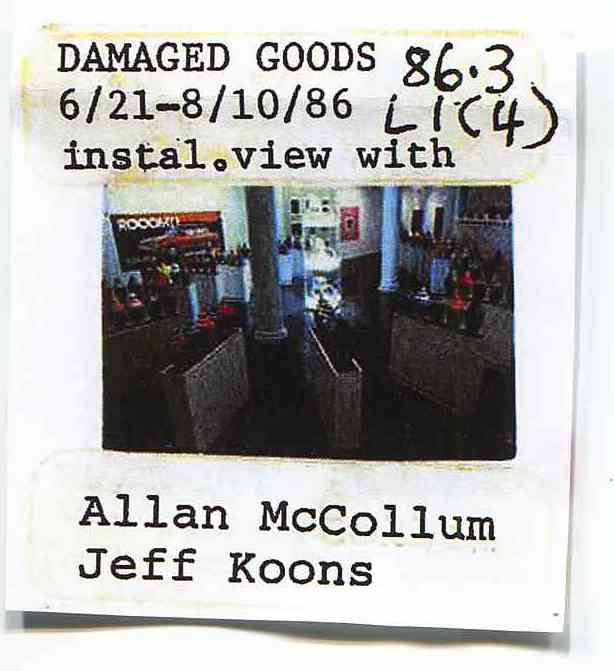

I pull out an image of Jeff Koons’s vitrines with vacuum cleaners and Allan McCollum’s Perfect Vehicles, from the 1986 New Museum of Contemporary Art show Damaged Goods. Pointing to the late 1980s and beyond, the slide, like the many Richard Princes, causes one to wonder again how Owens’s thinking may have progressed. His early death means that Owens remains, to us, a figure of the early 1980s, an avatar of postmodernism, even as his generation of critics has moved on to explore other practices and concerns. How would he have addressed the retrenchment in the years to come from the critical positions he and his colleagues staked out, the sensationalism of the Saatchi school, or the maximalism of the epic projection and spectacular photograph? A remark made by Owens to Stephanson on the subject of neo-geo is telling: “The whole thing has lost its criticality. It is not dissatisfied with anything.” 27

What was, for Owens, the difference between Koons and McCollum? Their work shared the entrance to Damaged Goods, an exhibition devoted to theme of the art commodity: both artists inscribed repetition and readymade forms into their work. Yet Owens chose to write on McCollum alone. In “Repetition and Difference,”28 he described the artist’s “Surrogates,” pseudo-paintings equivalent in appearance yet different in size, hence cost, as a critical reflection on the serial nature of the art market itself. (Seriality, Owens observed, “is both the definitive mode of late-capitalist consumer society and, since Warhol at least, the dominant model for art.” 29) Though Koons’s art was also serial, it was not sufficiently critical of this tactic; it did not attempt to “understand” its own relations of production but ironically affirmed them. Owens seems to have had no taste for irony (Warhol was an interesting exception). Rather, he “looked for doubt in practice,”30 in criticism, and in the classroom. Indeed, it would seem that one of the few things Owens did not doubt was doubt:

There was never a preconceived idea that Craig wouldn’t or couldn’t take apart. For example, Walter Benjamin’s “Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” essay. He asked, “Is this a great piece? Is it still relevant? Now that it’s accepted, is it true? Does it work?” He was an unorthodox thinker. Orthodoxy was his target.31

It is not easy to be reflexive, to challenge, even undermine, one’s ideas. Owens imagined one could. He did not always achieve this ideal. Indeed, his criticism, precisely because it takes risks, is often unresolved, contradictory. One finds a serious discrepancy between his claim that critics should avoid making judgments of taste and his proclivity to do just that (his clear preference for critical work is an example: “It’s irresponsible for artists not to make work that’s about the culture,”32 he told Horsfield and Blumenthal). Yet Owens made a concerted effort to examine his own practice and that of his peers. “The Discourse of Others” acknowledges the implicit sexism of postmodernist criticism, including his own. “Outlaws” examines his investment in feminism as a gay man. His interviews are punctuated by frequent expressions of dissatisfaction with his own work.

In “The Critic as Realist,” an essay on the literary critic Georg Lukacs, Owens called for the renewal of an engaged criticism. Recalling the examples of Diderot and Baudelaire, whose respective arguments for anti-theatrical painting and the depiction of “modern life” were fulfilled by David and Manet, as well as Lukacs’s passionate defense of Realism, he advocated an “activist” critical writing capable of “intervening in and directly shaping the development of art.” Rather than indiscriminately affirm the art of its time, criticism asserts its point of view, “prescribes remedies” for what it perceives to be art’s “deficiencies”:

Today we have come to suspect any form of critical intervention into artistic practice . . . with the result that serious critical activity has largely withdrawn from engagement with the production of art into history or “pure” theory. Given the noninterventionist policy of contemporary art criticism, the time has come . . . to reiterate Baudelaire’s plea for critical commitment.33

Although Owens wrote these lines in 1981, they resonate still; for at present an absence of articulated critical positions has left the market to determine much of what is seen and written about. As Hal Foster trenchantly observes in his recent collection Design and Crime, the past fifteen years have witnessed the replacement of the critic who evaluates new work by “dealers, collectors, and curators for whom critical evaluation, let alone theoretical analysis, [is] of little use.”34 The critic Jerry Saltz has also noted the passive tone of much current art writing, dryly observing that in the future ours will be seen as “an age where almost everything that was made was universally admired.”35

The supplanting of criticism by the market is an old story: one can find this very complaint in early debates around Pop, an art that attracted collectors before it established solid critical support. The fact that Pop remains interesting to us some forty years later confirms that critics’ judgments are not faultless, nor the market’s necessarily incorrect. And yet one would be hard put to disagree that criticism has lost its way. Criticism that seriously attends to the work’s form or its social meaning; criticism that argues intensely for or against a practice, that envisions what art could become; criticism that matters, criticism written as if criticism could matter, is rarely seen, or exists at the margins of awareness.

“The notion of crisis and that of criticism are very closely linked,” de Man once observed.36 Accordingly, criticism inevitably—or only—occurs in a crisis mode. De Man does not specify the circumstances that bring criticism to this troubled state. He suggests that the threat of criticism’s collapse is integral to criticism; indeed, it is an engine of it. De Man’s model of criticism as one subject to ebbs and flows of intensity cannot entirely account for the practice of art writing, a genre with a historical relation to the market, as Thomas Crow has argued in Painters and Public Life.37 Yet de Man’s conception is useful as we consider the retreat of art criticism as a powerful form, and the nostalgia for criticism—for the criticism of the 1960s and of postmodernism—that is now palpably felt. One may easily succumb to nostalgia for the purported vitality of prior epochs. (Benjamin, who knew all about it, speaks of the “indolence of the heart” of those who long for such a past.) Nostalgia is melancholic; it views the past as a loss. But criticism is opposed to nostalgia; it seeks to historicize the past, and come to terms with its own historicity.

The turn of the century has ushered in new media and artistic forms, as well as an internationalization of the market, of the exhibition, and of subject matter within the broader context of globalization. The dominance of projection, the spectacular photograph, and the large installation have been much noted but not sufficiently addressed. This is our situation; it is worth describing. Owens’s example encourages us not to turn away from the present but to engage it. There may well be no “right” moment for criticism. But as Owens suggests, it is precisely at such a time—when criticism seems most out of touch—that it again becomes most necessary.

- 1. Gregg Bordowitz, “The AIDS Crisis is Ridiculous,” in The AIDS Crisis is Ridiculous and Other Writings, 1986–2003, ed. James Meyer (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2004), 47.

- 2. Craig Owens, “From Work to Frame, or Is There Life After the Death of Author?,” in Implosion: A Postmodern Perspective, ed. Lars Nittve (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1987), 210; reprinted in Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power and Culture, eds. Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, Lynne Tillman, and Jane Weinstock (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 134.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. For the transcript of this interview, see Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield, eds., Craig Owens: Portrait of a Young Critic (New York: Baldlands Unlimited, 2018), 66–67.

- 5. Craig Owens, “Sherrie Levine at A&M Artworks,” Art in America 70, no. 6 (Summer 1982): 148; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 114.

- 6. Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983), 57–77; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 166–90.

- 7. Craig Owens, “Honor, Power, and the Love of Women,” Art in America 71, no. 1 (January 1983): 10; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 147.

- 8. Craig Owens, “Posing,” in Difference: On Representation and Sexuality (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1985), 7–17; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 201–17.

- 9. Gregg Bordowitz, quoted in a conversation with the author, 2002.

- 10. Mark Dion, quoted in a conversation with the author, 2002.

- 11. Jacques Derrida, “The Parergon,” trans. Craig Owens, October, no. 9 (Summer 1979): 3–41. See also Craig Owens, “Detachment from the Parergon,” October, no. 9 (Summer 1979): 42–49; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 31–39.

- 12. Craig Owens, “The Medusa Effect, or, The Specular Ruse,” in Barbara Kruger, We Won’t Play Nature to Your Culture (London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1983), 5–11; reprinted in Art in America 72, no. 1 (January 1984): 97–105; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 191–200.

- 13. Owens, “Honor, Power, and the Love of Women,” in Beyond Recognition, 143–55.

- 14. Owens, “Discourse of Others,” in Beyond Recognition, 166–90.

- 15. Craig Owens, “Outlaws: Gay Men in Feminism,” in Men in Feminism, eds. Alice Jardine and Paul Smith (New York: Methuen, 1987), 219–32; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 218–37.

- 16. Craig Owens, “Earthwords,” October, no. 10 (Autumn 1979): 127; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 46.

- 17. Ibid., 47.

- 18. Gregg Bordowitz, quoted in a conversation with the author, 2002.

- 19. Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” October, no. 12 (Spring 1980): 67–86; reprinted in Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed. Brian Wallis (New York and Boston: New Museum of Contemporary Art/ David. R. Godine, 1984), 203–17; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 52–69; and, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism Part 2.” October, no. 13 (Summer 1980): 58–80; reprinted in Art After Modernism, 217–36; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 70–87.

- 20. Owens, “Allegorical Impulse Part 2,” in Beyond Recognition, 85.

- 21. Bryson et al., “Editor’s Note,” in Beyond Recognition, 328.

- 22. Andrea Fraser, quoted in a conversation with the author, 2002.

- 23. Owens, “Discourse of Others,” in Beyond Recognition, 173.

- 24. Craig Owens quoted in Anders Stephanson, “Interview with Craig Owens,” Social Text, no. 27 (1990): 64; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 308.

- 25. Ibid., 310.

- 26. Owens, “Discourse of Others,” in Beyond Recognition, 173.

- 27. Owens in Stephanson, “Interview with Owens,” in Beyond Recognition, 315.

- 28. Craig Owens, “Allan McCollum: Repetition and Difference,” Art in America 71, no. 8 (September 1983): 130–32; reprinted in Allan McCollum, Surrogates (London: Lisson Gallery, 1985), 5–8; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 117–21.

- 29. Ibid., 118.

- 30. Barbara Kruger, quoted in a conversation with the author, 2002.

- 31. Mark Dion, quoted in a conversation with the author, 2002.

- 32. For the transcript of this interview, see Blumenthal and Horsfield, eds., Portrait of a Young Critic, 90.

- 33. Craig Owens, “The Critic as Realist,” Art in America 69, no. 7 (September 1981): 9–11; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 254–55.

- 34. Hal Foster, Design and Crime and Other Diatribes (London: Verso, 2002), 121.

- 35. Jerry Saltz, “Learning on the Job,” The Village Voice, September 10, 2002; reprinted in Jerry Saltz, Seeing Out Loud: The Village Voice Art Columns, Fall 1998–Winter 2003 (Great Barrington: The Figures, 2003), 19.

- 36. Paul de Man, “Criticism and Crisis,” in Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 8.

- 37. Thomas Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth Century Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985).