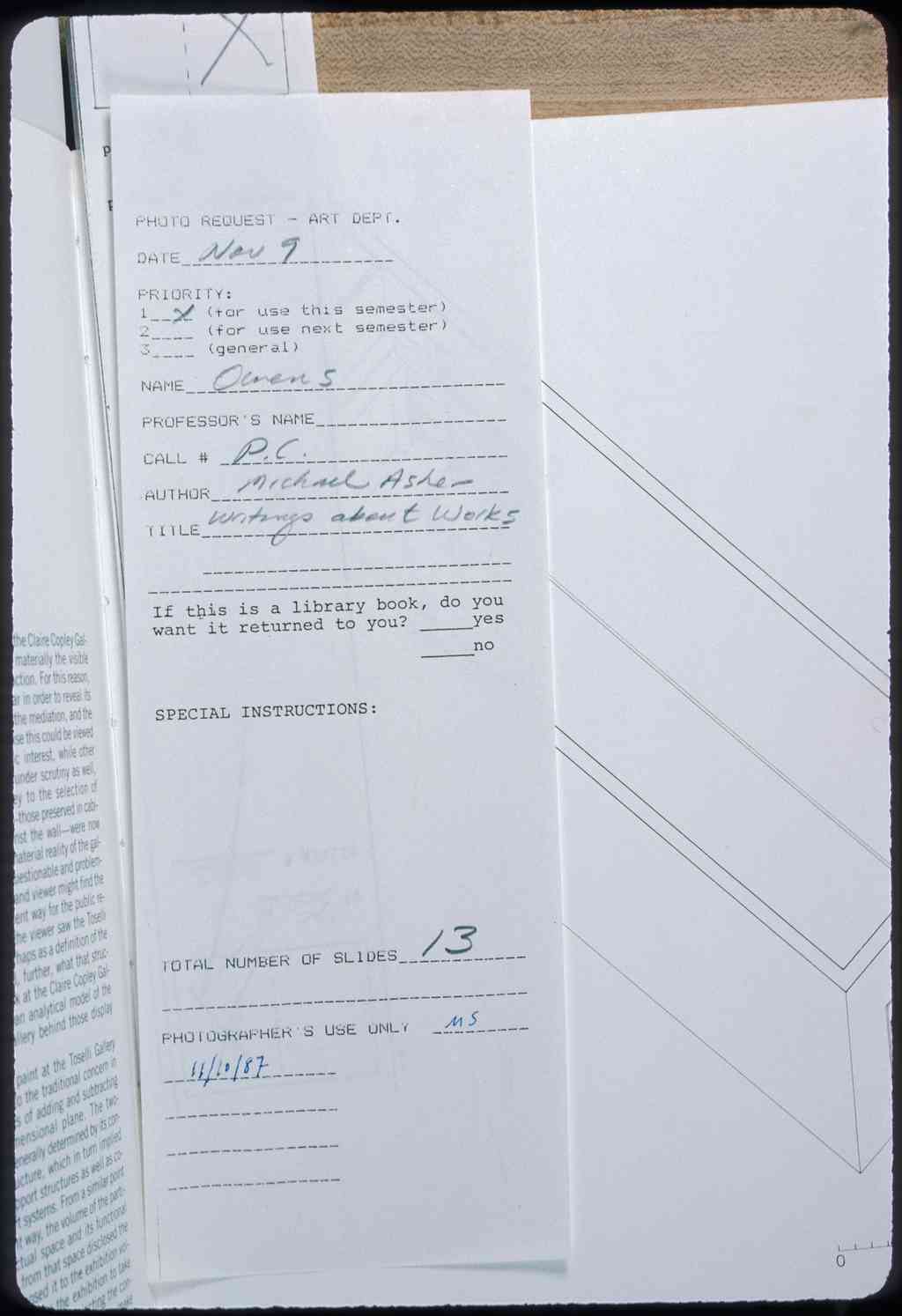

Michael Asher, Writings 1973–1983 on Works 1969–1979, with a photo request form, November 9, 1987; diapositive S202, collection de Craig Owens, conservée par James Meyer, Washington, D.C.

Far from advocating that artists should submit to the laws of the art market, the professionalism that Owens wished for art education in his cover letter of his Rochester application was directly tied to the “materialist cultural practice” he invoked in the conclusion of “From Work to Frame.” In response to the rise of the art market in the late 1980s and the institutionalization of certain art-critical practices that he had championed in his writings since the beginning of that decade, Owens promoted artistic practices and a mode of teaching that analyzed the conditions of production within the field of art. The courses he taught between 1987 and 1989 at Yale, the University of Virginia, and Barnard, as well as the seminar “The Political Economy of Culture” that he proposed to SAIC bear witness to this. The teaching program he developed for the University of Rochester expanded his deconstruction of the institutional framework conceived in light of the work of Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, and Hans Haacke in the 1970s to include a critique of cultural representations. The goal was to educate cultural producers by articulating an analysis of the political economy of the field of art that would lead to the promotion of socially and politically involved practices. The workshop “Visualizing AIDS” testified to a mobilization of academic institutions for activist ends as a way to address the urgency of the AIDS crisis.

Owens did not live long enough to see the institutional success of politically engaged critical thinking in the 1990s and the artistic practices associated with it, which cause some to doubt their capacity to present any kind of opposition within the field. As Janna Graham, Valeria Graziano and Susan Kelly point out: “In art institutions since at least the 1990s […], radical ideas have increasingly been packaged as a new kind of ‘content capitalism’, deliberately separated from their immediate contexts and the politics they name.”154 Owens had nevertheless foreseen the traps of institutional appropriation already in the mid-80s. In “The Problem with Puerilism,” published in 1984, he observed: “The appropriation of the forms whereby the subcultures resist assimilation is part of, rather than an antidote to, the general leveling of real sexual, regional, and cultural differences and their replacement with the culture industry’s artificial, mass-produced, generic signifiers for ‘Difference’.”155

In her essay “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy” (2010), the artist Hito Steyerl, in admission “that [she her] self may bow [her] head in shame, too,” considers that “the politics of art are the blind spot of much contemporary political art.” In a time of post-democratic globalization, when “deconstructivist contemporary art museums pop up in any self-respecting autocracy,” she maintains that it is more necessary than ever to support “a quite extensive expansion” of Institutional Critique. For Steyerl, these artistic practices are fully pertinent to confront the urgent, problematic issues that art production faces when “squarely placed in neoliberal thick of things.” She argues that contemporary art in fact enables “the development of a new multipolar distribution of geopolitical power whose predatory economies are often fueled by internal oppression, class war from above, and radical shock and awe policies.”156 Like Owens, Steyerl believes that a critical analysis of the political and economic conditions of artistic production remains more relevant than ever, and cannot simply be relegated to a bygone era.

To forge a “materialist cultural practice” that “subverts and subordinates to itself the conditions from which it stems,” and that articulates the conditions for the production of art to a critique of the representations of our society thus constitutes a theoretical and educational program that is still worth pursuing today. In light of the corporatization of art institutions and the subjection of institutions of higher education to a profit criterion, it is more necessary than ever to develop strategies to mobilize and hold accountable the institutions in which each one of us is involved. The rise of conservatism associated with the paradoxical institutional appropriation of the questions raised by cultures that have traditionally been minoritized by the institutions themselves pushes us to recall Owens’s exhortation: “we ourselves are to employ, rather than simply being employed by, the apparatus we all – ‘lookers, buyers, dealers, makers’ [to which we should add professors and students] – are threaded through.”157

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

- 14.

- 15.

- 16.

- 17.

- 18.

- 19.

- 20.

- 21.

- 22.

- 23.

- 24.

- 25.

- 26.

- 27.

- 28.

- 29.

- 30.

- 31.

- 32.

- 33.

- 34.

- 35.

- 36.

- 37.

- 38.

- 39.

- 40.

- 41.

- 42.

- 43.

- 44.

- 45.

- 46.

- 47.

- 48.

- 49.

- 50.

- 51.

- 52.

- 53.

- 54.

- 55.

- 56.

- 57.

- 58.

- 59.

- 60.

- 61.

- 62.

- 63.

- 64.

- 65.

- 66.

- 67.

- 68.

- 69.

- 70.

- 71.

- 72.

- 73.

- 74.

- 75.

- 76.

- 77.

- 78.

- 79.

- 80.

- 81.

- 82.

- 83.

- 84.

- 85.

- 86.

- 87.

- 88.

- 89.

- 90.

- 91.

- 92.

- 93.

- 94.

- 95.

- 96.

- 97.

- 98.

- 99.

- 100.

- 101.

- 102.

- 103.

- 104.

- 105.

- 106.

- 107.

- 108.

- 109.

- 110.

- 111.

- 112.

- 113.

- 114.

- 115.

- 116.

- 117.

- 118.

- 119.

- 120.

- 121.

- 122.

- 123.

- 124.

- 125.

- 126.

- 127.

- 128.

- 129.

- 130.

- 131.

- 132.

- 133.

- 134.

- 135.

- 136.

- 137.

- 138.

- 139.

- 140.

- 141.

- 142.

- 143.

- 144.

- 145.

- 146.

- 147.

- 148.

- 149.

- 150.

- 151.

- 152.

- 153.

- 154. Janna Graham, Valeria Graziano, Susan Kelly, “The Educational Turn in Art: Rewriting the Hidden Curriculum,” Performance Research, “On Radical Education,” vol. 21, no. 6 (December 2016), 30.

- 155. Craig Owens, “The Problem with Puerilism,” Art in America (Summer 1984); reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 266.

- 156. Hito Steyerl, “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the transition to Postdemocracy,” e-flux, no. 21 (December 2010), online : https://www.e-flux.com/journal/21/67696/politics-of-art-contemporary-art-and-the-transition-to-post-democracy/ accessible October 15, 2019.

- 157. Craig Owens, “From Work to Frame,” 136.