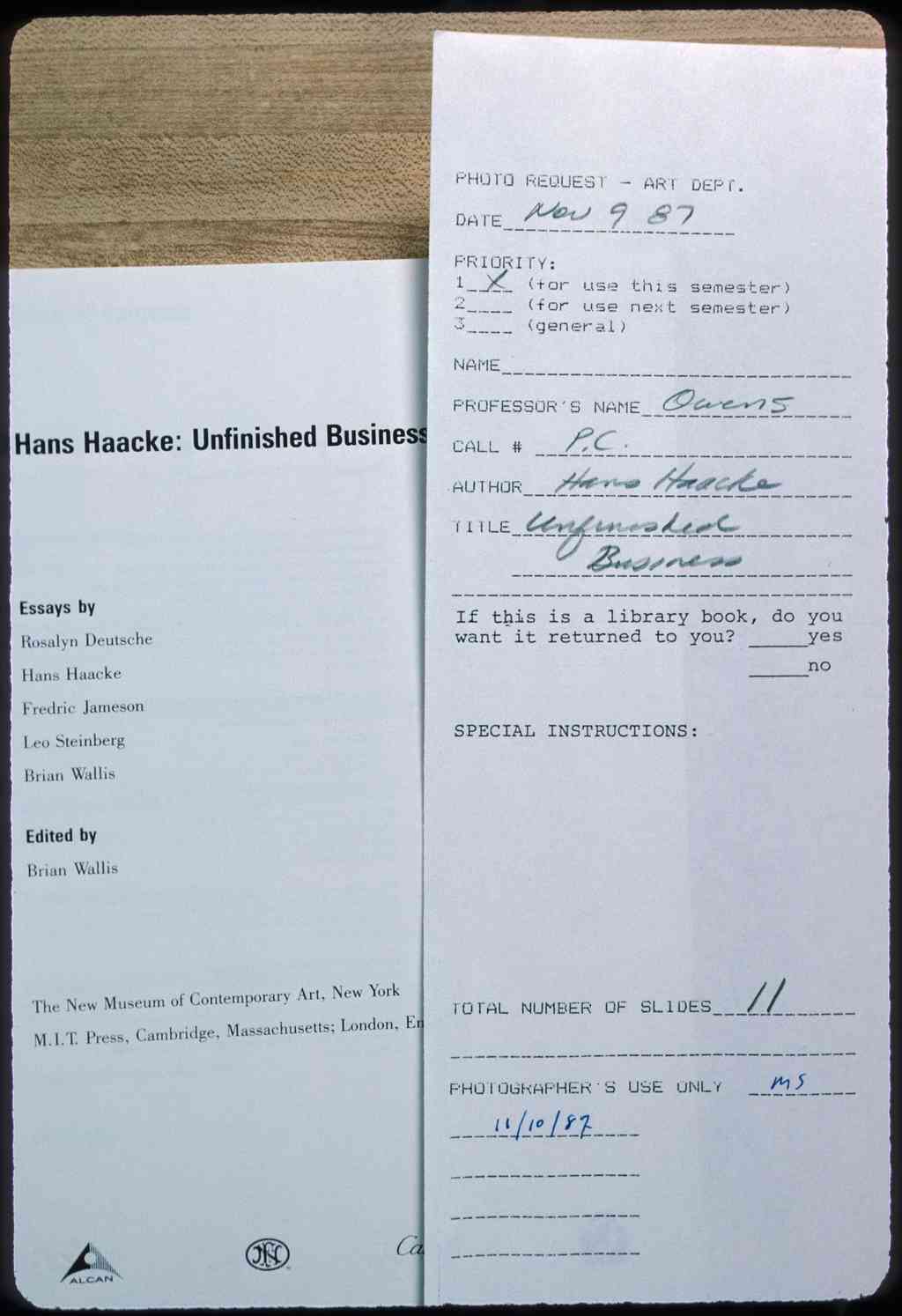

Slide no. 203, View of Hans Haacke, Unfinished Business, ed. Brian Wallis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 5, with a photo request form, dated from November 10, 1987. Craig Owens Slide Library, held by James Meyer, Washington, D. C.

As the implementation of the Bologna agreements took place with the aim of harmonizing higher education in the European Higher Education Area in the 2000s and thereby reconfiguring it to make it more competitive in the global knowledge economy,1 art education became an obsessed upon topic of discussion in the contemporary art world. The emergence of the term “Educational Turn” in the early 2010s to refer to artistic and curatorial practices that adopt pedagogical formats and procedures for producing and sharing knowledge as well as delving in to broader educational praxis, has been symptomatic of this new fascination.2 These research-based practices, with their emphasis on process and discursive interventions rather than object production, have intersected with the emergence of the figure of the “artist-researcher”3 in discussions about their capacity to produce, or not, a space of emancipation that escapes the neoliberal reification of the cultural field and the profit-driven mutation of higher education within the framework of cognitive capitalism.

In this process of transformation that has affected the figure of the artist, theory and re-evaluation of its place in art education have played a fundamental role. In France since 2010, the emphasis has been placed on its teaching in art schools as a necessary condition for the awarding of a Master’s degree, in particular by imposing the completion of a research dissertation by students during the two last years of their course and the recruitment of teachers who have attained a PhD.

In order to reflect on this period of reform in art education, which gave rise to much controversy within French institutions, it may be interesting to take a step back and regard, in order to form some perspective, the pedagogical context of the United States. There, theoretical teaching in art education progressively gained in importance and recognition after the Second World War – the European reform having been largely inspired by the Anglo-Saxon model. More precisely, the period of the 1970s and 1980s is often presented as a key moment for the articulation of art and theory in America: the New York magazine October, created in 1976 by Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson, notably advanced itself to the front line of the renewal of critical thinking on art by participating in the invention of a new form of theoretical art criticism and contemporary art history nourished by French Theory. This approach fully participates in what many authors have described as the “golden age” of Theory and which corresponds to the enthusiasm hitherto generated in the English-speaking world by the translation of French authors such as Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan.4

The figure of Craig Owens (1950-1990) provides an interesting entry point into this New York-centric scene. In addition to having contributed fully to this history of Theory in the art field, teaching young artists was for him “a necessary part of his project”.5 Although known for his texts published in October in the late 1970s, such as “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,”6 Owens did not receive the same recognition as his contemporaries, such as Douglas Crimp and Hal Foster, partly due to his premature death from AIDS. His trajectory, though short, was nevertheless rich in theoretical ideas. Quickly distancing himself from October in the early 1980s, Owens developed through his writings a theoretical program that combined references to French post-structuralism with ideas influenced by feminist, postcolonial, cultural, visual and queer theories, thus participating in a theoretical adventure that would go on to find a massive echo in the art world from the 1990s onwards.

As an art critic, theorist, editor, translator and teacher, Craig Owens was at the crossroads of professional and academic circles. Following the path of his theoretical and pedagogical practices thus offers an excellent insight into the process of bolstering theory that was taking place at the time, both in artistic practices and in art education in the United States. In 1979, in his essay “Earthwords”, Owens identified the link between the “eruption of language into the aesthetic field” and the emergence of postmodernism.7 As Howard Singerman explains, this phenomenon goes hand in hand with the rise of discursivity in art education in the 1970s and 1980s, which he understands as a sign of its new found proximity to the academic field, language being the decisive attribute of the university, and which he considers the main point of the MFA.8 It is also not insignificant that many of Owens’s former students, such as Andrea Fraser, Gregg Bordowitz, Mark Dion and Tom Burr, who gained visibility in the early 1990s as a new generation of artists renewing the practices of institutional critique, and who extol the importance of his theoretical teaching in their own careers, make writing and theorizing an important part of their own artistic practice.

This dossier therefore focuses on Craig Owens’s teaching practice and its articulation with his work as an art theorist and critic. It opens with the essay “For a ‘materialist cultural practice’. Craig Owens and Art Education”, which discusses Craig Owens’s pedagogical approach, tracing the milestones in his thought process. In particular, it focuses on the way Owens attempted to articulate a critical understanding of the conditions of production within the art world and the professionalization imperatives he upheld in order to enable his students to critically situate themselves in the art world.

The dossier then focuses on Owens’s slide collection, which is one of the few archives to have survived and which came to us through James Meyer, art historian and curator at the National Art Gallery in Washington D.C., and who still conserves it today. Symptomatic of the erasure that characterized the catastrophe that was the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, there is no official archive dedicated to Craig Owens. The texts he published during his lifetime in exhibition catalogues and journals constitute the main resources that enable us to follow the path of this young intellectual. Sensing the fragility of this legacy, his friends Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, Lynne Tillman and Jane Weinstock gathered his most significant theoretical texts in the collection Beyond Recognition. Representation, Power, and Culture, published as early as 1992 by the University of California Press, as the only means of keeping his voice aloud in the field, despite Owens’s own reluctance to publish such a book in which the essays are decontextualized. For this reason, this dossier provides a chronology and a bibliography based on the varied information gathered during the course of this investigation.

In addition to its unique status, Craig Owens’s slide collection is an archive that was assembled at the crossroads of its owner’s activities as a teacher, editor of Art in America and art critic. “Outside the Box: James Meyer Unpacks Craig Owens’s Slide Library (Writing the ‘80s)”, originally published in Artforum in 2003, presents an overview of the archive understood through the different roles Craig Owens occupied in the 1980s. The text “‘So useless, so useful’. On Craig Owens’s slide collection” by Nathalie Boulouch relocates it in a history of the pedagogical use of slides in art education.

In “Elusive Affiliation: Craig Owens and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick”, David Deitcher returns to the dialogue between the two authors on the importance of the intersection of feminist and queer identities and politics.

Finally, this investigation could not have been carried out without the testimony of those involved in the first place: artist Tom Burr recalls various moments of Owens’s teaching in his essay “Architecture of influence: Thinking through Craig Owens” originally published in Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory in 2016. Andrea Fraser introduces notes from Craig Owens’s classes at the School of Visual Arts and Craig Owens’s own annotated copy of her first article “In and Out of Place” published in Art in America in June 1985.

The publication of the research presented in this dossier on the website of the Master’s degree section: “Holobionte. Pratiques visuelles, exposition, et nouvelles écologies de l’art” (“Holobiont. Visual practices, exhibitions and new ecologies of art”) recently structured in order to give visibility to the pedagogical approach developed by a group of professors at the Grenoble location of the Ecole supérieure d’art et design, is the result of an informed decision. The questions associated with visual practices, social justice, the economy of art and the critical economy of knowledge raised by Owens’s teaching also inform the pedagogical and research practices carried out within this specialised section as well as in the research unit entitled: “Hospitalité artistique et activisme visuel pour une Europe diasporique et post-occidentale” (“Artistic hospitality and visual activism for a diasporic and post-Occidental Europe”) to which it is attached. This dossier thus does not so much seek to present Owens’s pedagogical practice and the period in which it unfolds as a model, but rather as an “unfinished business” that is still relevant in the current period. A set of dynamics and methodological investigations that emanate from this research actively enter into dialogue with our pedagogical practices today. It is also for this reason that a collection of Owens’s texts, entitled Le discours des autres and introduced and translated into French by Gaëtan Thomas, will soon be released by the publisher Même pas l’hiver, in order to facilitate access to these texts for a French readership, and more particularly for art school students.

Being a living and ephemeral practice, pedagogy is difficult to study as an anatomical object. The presence of this dossier on this website is thus conceived as a living space for artistic and curatorial experimentation, which nourishes the work within the Holobionte Master’s degree section, while also allowing itself to be contaminated by it. In this spirit, it constitutes a space for experimentation which may see new extensions added according to the future projects that Holobionte will host.

Acknowledgements

The dossier, presented here, stems from the research program “Art, théorie et pédagogie critique : Tirer un enseignement de Craig Owens” (“Art, Theory and Critical Pedagogy: The Legacy of Craig Owens”) led with Dean Inkster within the framework of ÉSAD – Grenoble – Valence and supported by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication from 2014 to 2016. This program enabled the organization of a research seminar in partnership between ÉSAD and the École du Magasin and collaboration with the Master program Critique-Essais of the University of Strasbourg under the direction of Janig Bégoc, whose students organized a study day on the 30th of March 2015 entitled “Entre dissolution et réinvention de l’image : enquête sur la place de l’allégorie dans l’art contemporain et les ‘Visual Studies’” (“Between dissolution and the reinvention of the image: an investigation into the place of allegory in contemporary art and ‘visual studies’”). This research program also benefited from the collaboration with the Archives de la Critique d’art and the University of Rennes 2 in the framework of the international seminar: “La circulation des stratégies discursives entre la critique d’art américaine et européenne après 1945: une autre guerre froide ?” (“The circulation of discursive strategies between American and European art criticism after 1945: another cold war?”) organized in 2015 with the support of the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Thanks to all the contributors Nathalie Boulouch, Tom Burr, Andrea Fraser, David Deitcher, James Meyer, as well as Douglas Crimp, Rosalyn Deutsche, Mark Dion, Peter Eisenman, Silvia Kolbowski, Elizabeth Baker, Lynn Tillman, Jane Weinstock, Marina Zurkow, Janig Bégoc, Rainer Oldendorff, Michael Sohn, Gayle Day, Pierre Leguillon, Niels Norman, Estelle Nabeyrat, the students of session 24 of the Ecole du Magasin, Nicolas Fourgeaud, Noura Wedell, Claudio Cambon, Elizabeth Rathgen, Edgar Tom Stockton, Alex Lamarche, the documentalists of the Fales Library, of the School of Visual Arts, of Rochester University and of Yale University, as well as Benjamin Seror, Antoinette Ohannessian, Pascale Riou, Camille Barjou, Simone Frangi and Marc Lenglet.

- 1. See the communication from the European Commission “The role of the universities in the Europe of knowledge,” available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52003DC0058&qid=1645707872224&from=EN

- 2. See Irit Rogoff, “Turning,” e-flux, no. 0 (November 2008), online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/00/68470/turning/; Curating and the Educational Turn, eds. Paul O’Neill, Mick Wilson (London: Open Editions / de Appel, 2010); Janna Graham, Valeria Graziano, Susan Kelly, “The Educational Turn in Art: Rewriting the Hidden Curriculum,” Performance Research. A Journal of the Performing Arts, vol. 21, no. 6 (2016), 29–35.

- 3. See for example Howard Singerman, Art Subjects, Making Artists in the American University (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999); Sandra Delacourt, Katia Schneller, Vanessa Theodoropoulou, Le chercheur et ses doubles (Paris: B42, 2016).

- 4. See for example Jean-Michel Rabaté, The Future of Theory (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002); “The Future of Criticism: A Critical Inquiry Symposium,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2, (2004): 324-479; Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2 (2004): 225-248; T. Eagleton, After Theory (London: Penguin, 2003); Theory’s Empire. An Anthology of Dissent, eds. Daphne Patai, Will H. Corral (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005); Jane Elliott, Derek Attridge, “Introduction: theory’s nine lives,” in Theory After ‘Theory’, eds. Jane Elliott, Derek Attridge (New York: Routledge, 2011), 1–16.

- 5. “Editor’s Note”, in Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition. Representation, Power, and Culture, eds. Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, Lynne Tillman, Jane Weinstock (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 328.

- 6. Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” October, no. 12 (Spring 1980): 67-86; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 52–69.

- 7. Craig Owens “Earthwords,” October, no. 10 (Autumn 1979): 120–130; reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 45.

- 8. See Howard Singerman, “Professing Postmodernism,” in Art Subjects, 155–186.