“[A]rt education is failing its students.”1 It was with this acerbic remark that Craig Owens (1950-1990) began the cover letter for his candidacy for a teaching position in the art department at the University of Rochester in 1989, the last position he would hold before his premature death from an AIDS-related illness in 1990. By that time, Owens had already amassed ten years of teaching experience, mostly in New York City at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) (1983-1987), and at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Program (ISP) (1984-1987).

However, his comment on the failings of art education were based on his recent experiences, from 1987 to 1989, as an assistant, visiting, or adjunct professor in the prestigious art and art history programs of Yale University, the University of Virginia, Barnard College, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.2 Owens felt that these mainly academic programs focused primarily on the development of technical ability, style, and individual artistic vision. He believed that art education should instead offer a pedagogical framework “in which cultural activity is seen not as self-exploration and self-expression, but as a profession.” In summarizing his own approach to teaching, he added: “The point is to provide students with a usable knowledge of what working as—as opposed to simply ‘being’—an artist or critic entails.”3

Writing a cover letter is of course an act of persuasion. Applicants try to capture the attention of the jury while providing a suitable response to the expectations set forth by the recruiting committee, and, at the same time, to highlight their experience and abilities. As evidenced by the number of teaching proposals Owens made in the remainder of his letter, the stakes were very high, suggesting that he was seeking a more stable, tenured position with better health insurance than the lectureships he had held in the previous two years, and providing evidence of his willingness to enter the academic world. At the same time, the “professionalizing” view of art education that Owens advocated for is consistent with his own theoretical and critical approach and professional development in the 1980s as an art critic and editor at Art in America.

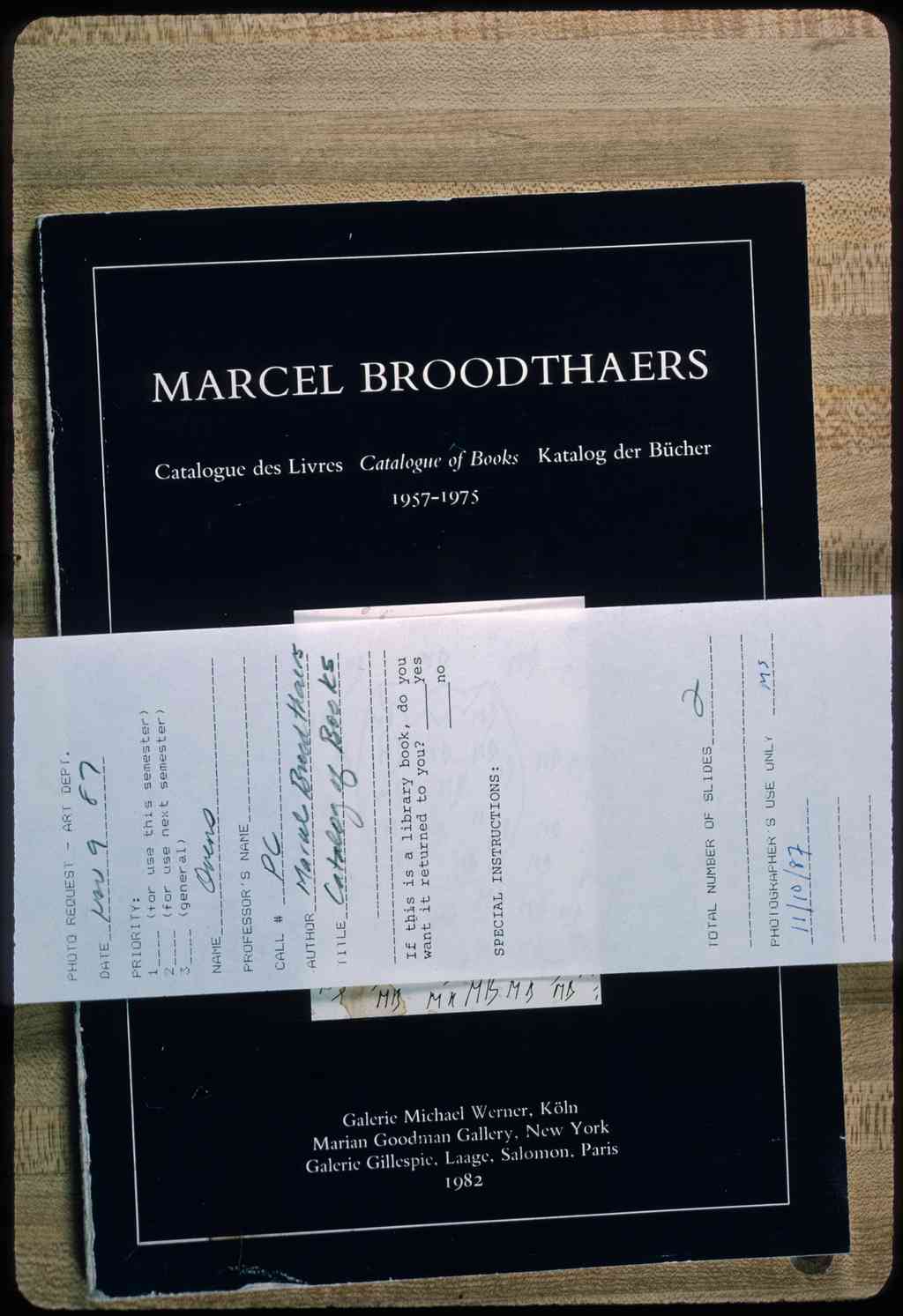

To understand how this view emerged in his teaching, one must first acknowledge the inherent problem of reconstructing the teaching process, which exists primarily as an experience between a professor and their students and, as such, goes largely undocumented. This is all the more difficult in Owens’s case, as unfortunately his personal archives were not preserved after his premature death from AIDS. We can nevertheless trace the final phase of his teaching career from the few artifacts that have been preserved: the cover letter and resume submitted to Rochester, held in the Lynne Tillman Papers at the Fales Library at New York University; his slide collection, which his partner, Scott Bryson, bequeathed to the art historian James Meyer, and the syllabi and bibliographies published in Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture. The editors devoted the final section of this anthology of Owens’s writing to pedagogy, which they felt represents “a necessary part of his project.”4

Teaching and intellectual inquiry were in fact closely linked throughout Owens’s career. Retracing his work as a teacher is essential to understanding both his view of art education and the development of his theoretical approach during his last three years, given that he stopped publishing in 1987—the exception being a short report of a symposium published in 1989 in the pages of Art in America.5 To understand the issues underlying the concept of “professionalism” that he advocated for in his cover letter to the University of Rochester, it is important to consider the context in which Owens offered his diagnosis of university art education. Secondly, paying attention to the theoretical teaching he developed from 1987 to 1989 helps envision how he linked art education to a “professional” practice reflecting on the art world structuration. Finally, examining the proposals he made in his application to the art department at the University of Rochester and the teaching he planned to carry out there, offers a glimpse of the theoretical approaches and questioning Owens seemed to be turning at the time, one that would accompany his understanding of art education, just as his career came to an abrupt end.

1. Towards an Analysis of the Economic and Political Conditions of Artistic Production

2. Treating Cultural Activity “as a profession”: Owens’s Teaching of Theory between 1987 and 1989

3. Educating Cultural Producers: Teaching Proposals project for the University of Rochester

- 1. Craig Owens, Final version of cover letter to the University of Rochester, written some time between the end of 1988 and the beginning of 1989, in anticipation of the academic year 1989-1990 (subsequently referred to as CLUR). Lynne Tillman Archives; MSS-180, Box: 32; Folder: 2; Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University Libraries.

- 2. See “Craig Owens’s Chronology” in this collection.

- 3. Craig Owens, Final version of the CLUR.

- 4. “Editors’ Note,” in Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture, eds. Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, Lynne Tillman, Jane Weinstock (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 328.

- 5. Craig Owens, “The Global Issue: A Symposium,” Art in America (July 1989); reprinted in Beyond Recognition, 324–328.